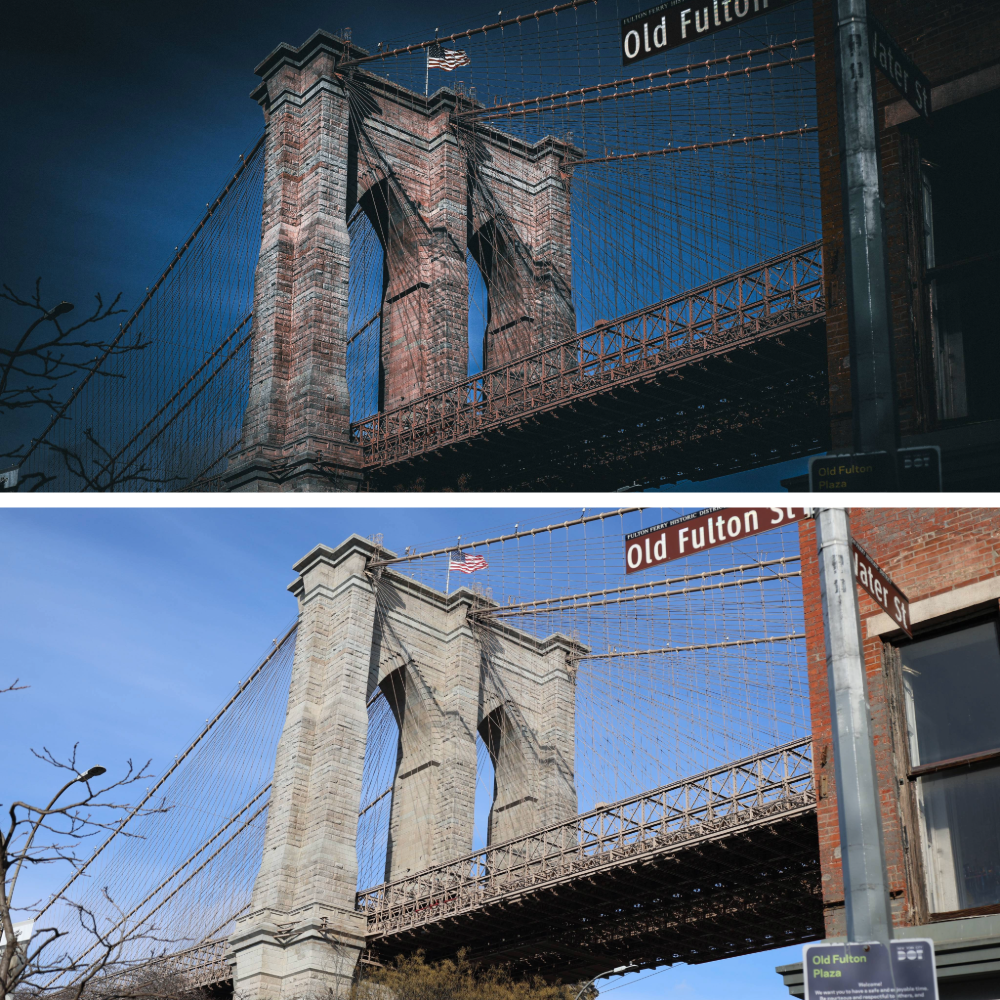

Landscape Post-Processing: Two Takes on One Bridge

The Brooklyn Bridge is a landscape whether we admit it or not, a man-made one, but still shaped by light, weather, scale, and time. Standing on Old Fulton Street, the raw capture comes first, and it does its job well. The sky is clean and blue, the stone towers are pale and accurate, the steel cables stretch across the frame with technical precision. Everything is readable, factual, and balanced. This is the camera doing what it’s designed to do: record information. The original image holds the structure together, preserves the geometry, and gives you a neutral starting point. Without this step, landscape post-processing turns into guesswork. You need a solid, honest file before you can even think about interpretation.

Post-processing is where that neutral record starts to bend toward intention. In the processed version, the sky deepens and gains weight, shifting from a passive background to an active part of the scene. That single change alters the entire hierarchy of the image. The bridge immediately feels more dominant, more monumental. Contrast is shaped rather than increased blindly, pulling texture out of the stone blocks so they feel aged and heavy, while the steel structure gains definition without turning brittle. Shadows are allowed to settle instead of being lifted into flatness, and highlights are restrained so the scene doesn’t drift into postcard brightness. Nothing here invents a new reality, but the emphasis moves from documentation to atmosphere.

This is the core of landscape post-processing: deciding what the viewer should feel first. The original photograph answers practical questions about place and light. The processed image answers emotional ones. Was the bridge imposing or casual? Did the sky feel open or pressing down? Did the scene carry calm or tension? These aren’t things the sensor understands on its own. Post-processing becomes a form of translation, taking the memory of standing there and expressing it through tone, color, and contrast. The American flag, small in the frame, suddenly matters more once the surrounding tones darken. The cables read sharper against the sky, reinforcing the sense of structure and order. Even the edges of the frame play a role, subtly guiding attention back toward the arches and towers.

What matters is restraint. Good landscape post-processing doesn’t shout. It nudges. Push too far and the image turns theatrical, disconnected from the place it came from. Pull back too much and it stays polite, forgettable. I often move sliders past where I think they should go, then walk them back slowly, watching for the moment when the image starts to feel like how the place actually felt, not how software thinks it should look. The goal isn’t realism in the technical sense, but believability in the emotional one.

Landscape photography doesn’t end when the shutter clicks. That moment only captures raw material. Post-processing is where the landscape becomes legible as an experience rather than a record. Whether it’s a mountain range or a steel bridge cutting across the sky, the principles stay the same. Shape the light, respect the structure, and let the final image say something the original file couldn’t quite say on its own.